The Bloody Birth of Europe (MT25)

Introduction

“Do not follow the bad example I have set you; I have often undertaken war too lightly and sustained it out of vanity. Do not imitate me but be a peaceable prince.” - Louis XIV, on his deathbed in 1715.

Upon the cannons of the French kingdom during the reign of the Sun King was written “The Final Argument of Kings”; “Ultima Ratio Regum”. We shall see many of Kings make their “final arguments” here, for the birth of Europe, the beginning of modernity, was marred in fire and blood, in wars for king and God. The argument laid out here was best articulated by Charles Tilly - “war made the state”. Our beginning here is not a clean nor glorious one, but one filled with internecine conflict, sectarianism, and a great crisis sweeping the continent. The way in which the nations of Europe dealt with the peculiar challenges of the period would later define their national characters, for it is in the struggles of this era that the roots of ideologies as diverse as Swedish social democracy, Francoism, English liberalism, and Bismarckism lie. And indeed, Bismark himself expressed this most insightfully; for the legacies of Europe, not Germany alone were forged in iron and blood, and rest on foundations of violence and ruin, from which a new order emerged.

Before we open our discussion of the main front of struggle, let us consider the conditions from which these struggles and issues emerged. Europe in the 16th century faced triple winds of change emerging from technological and demographic factors: the Agricultural Revolution, the colonisation of the Americas, and the shifting of the Baltic Trade. Let us address each one in turn, in order of their significance.

The Agricultural Revolution, especially in the lands of the Holy Roman Empire, but also across the continent, such as in Britain, led to a combination of both rapid economic growth (by pre-industrial standards) and declining real incomes for most of the population through the proto-mechanisation of large sections of agriculture. In many ways, the Agricultural Revolution was the driving force which eroded feudalism. The advancement of the European mode of production led to the growth of towns supported by increasingly productive countryside; it also created incentives for marketisation and trade in agricultural products, which gave commercial agriculture an advantage over feudal forms, at least west of the Elbe.

The colonisation of the Americas, meanwhile, set off the Price Revolution through the expansion of money supply significantly; the arrival of Spanish treasure fleets ended the great drought of bullion that had existed before the discovery of the New World. The increase in money supply provided the basis for new forms of European credit and the creation of increasingly sophisticated financial instruments. Take, for example emergence of the modern bank in the Italian city-states, whose merchants served as the intermediaries for this massive flow of money from the colonies to the metropole.

The pressure of the Baltic Trade is a particularly interesting point, emerging from the consolidation of the Polish polity through the mediation of Catholicism. The pressure of German conquest had forced the consolidation of the Polish and Lithuanian polities, and their unification to drive Western forces out. The economic settlement forced by the Rzeczpospolita through the elimination of their privileges crippled the Hanseatic League’s main power base in terms of trade and had forced their decline in favour instead of British and Dutch merchants who had more favourable access to New World - and East Indian – wealth. The low countries and Britain also benefitted in this competition from the maritime traditions of both states, something which did not exist in the Holy Roman Empire (largely due to the concentration of political power in agricultural Austria after the Wars of the House of Luxembourg destroyed much of the wealth of North Germany and Bohemia).

All three factors contributed to the growth of capitalist forms of production in Western Europe, and (to a lesser extent) in Eastern Europe. Another major contributor to this shift was the printing press, which would amplify these trends through the rapid transmission of knowledge. It also birthed prototypical mass politics in the form of widespread propaganda in the form of pamphlets and, of course, various translations of the Bible.

The Bloody Birth of Europe

The struggle of this period is primarily a class struggle, waged through the proxies of faith and geopolitics. The two main classes which we must concern ourselves with are the urban burghers and the rural nobility. As discussed, the technological, demographic, and colonial developments of the prior century had bolstered the growth of towns and cities and had begun to make them a powerful political force in the most developed states of the continent. There were ill-fated attempts by this class to seize power in other parts of Europe - most notably the Czartoryskis (the noble governors of Warsaw) in Poland, supporters of the Saxon monarchy - but they had largely failed outside of the Germanic states and France.

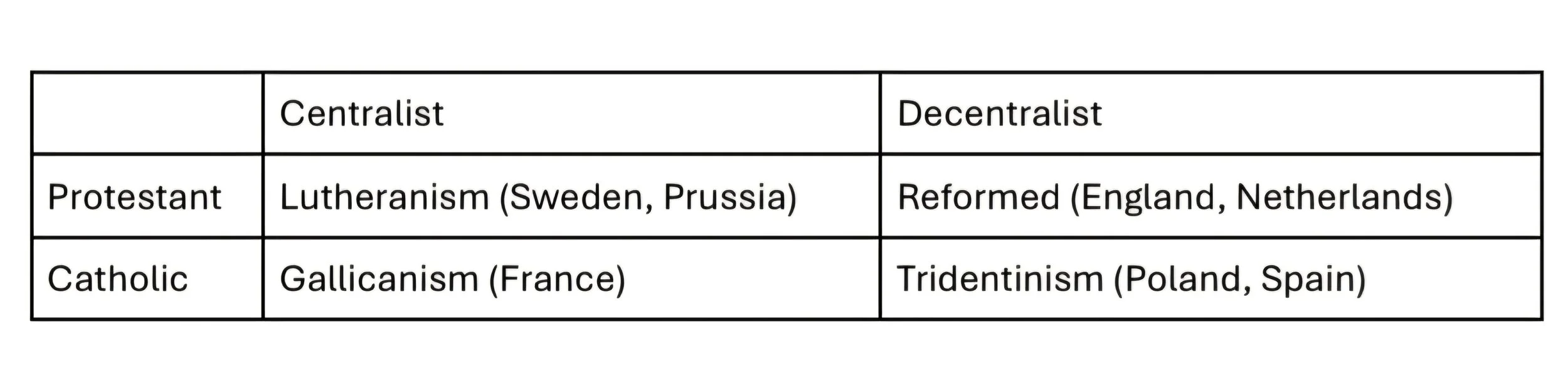

In the understanding of the class dynamic, we must also understand the confessional dynamic, for the faith of a society makes a society of its faith. Faith serves as the beating heart of a society’s philosophy and as the basis of its legitimation and development. In the world of early modernity, Calvinism, Lutheranism, and Catholicism can be said to have constituted meta-ideologies, standing not merely as ideological currents on which various groups battled, but as the very basis on which those groups saw the world. The matter of the Protestant states is relatively simple, at least in comparison to Catholicism. We may examine the various political models of early modern Europe in the following matrix:

The Catholic states show in many ways a heterogeneity depending on the relationship of the particular state to the Church both within and without its borders. It may be argued that countries such as France - and France is the archetypical example of this trend - were able to exert significant control of their branches of the Catholic Church without resolution to Protestantism. The nature of the deference to the state and earthly authority preached by men such as Martin Luther made Lutheranism popular among statist governments, while the iconoclasm and most importantly the promotion of the virtue of labour (the so-called “Protestant work ethic”) of the Calvinists made Calvinism popular among the states in which the bourgeoisie had the strongest control.

Central Europe

Let us now zoom in and take stock of the individual struggles within the continent. Of course, there exists a dialectic between the national and international struggles between the classes in this time period; thus it may be more accurate to say that what we are looking at are not sets of isolated events occurring in isolation, but rather case studies and flashpoints in the broader European struggle. The heart of this battle for institutional control, and certainly its most violent expression, was in the Holy Roman Empire, which had, after the loss of its territories in Northern Italy, recognised officially at the 1512 Diet of Cologne, proclaimed itself the “Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation”, or, informally to others across the continent, “Germany”. Within the so-called “German Nation” (which, in reality, included not just modern-day Germany but also modern-day Switzerland, Austria, Czechia, Low Countries, and parts of Poland and Denmark) a great struggle brewed. The follies of King Sigismund and his schemes against his own family, and the consolidation of the Polish margraves weakened the North German power base. This fostered an era of South German dominance, expressed most notably in the rise to power of the Habsburgs. But the North Germans had not been stripped of total political power; the Hansa allied themselves with the Schmalkaldic and Protestant element, and as the tides of Reformation swept in, so did a battle between mercantile-artisan North Germany and agricultural South Germany. This divide would reassert itself in the centuries to come, from the Deutscher Bruderkrieg to the strength of the CSU and Bavarian autonomism even today.

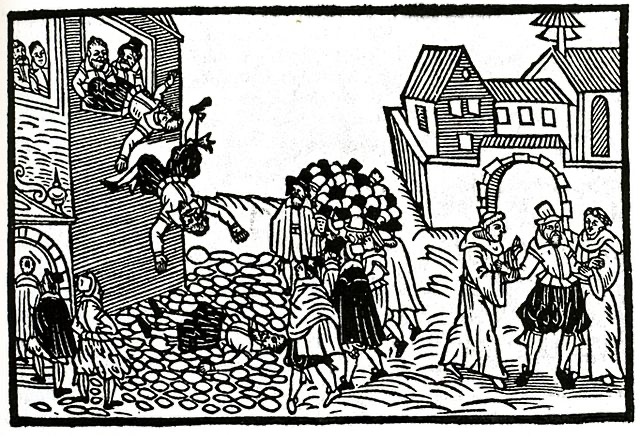

But notably the opening shots of the Thirty Years’ War were not fired in Germany; they came from Czechia. Arguably, the Reformation itself was born in there, courtesy of the theologian Jan Hus, who proved himself one of the greatest enemies of the Sigismund when Hussite armies rose to battle the Imperial throne. While they were defeated, the Czechs remained rebellious and discontented, becoming known for their practice of throwing heretics out of windows. And it was, of course, the Third Defenestration of Prague which began the hostilities of the Thirty Years’ War, for while the Lutherans had won concessions at Augsburg, many had feared that the concessions were merely temporary given the continued Catholic rule of the Empire. They were proven right in many respects when Ferdinand II infringed on the religious freedoms of the Czechs, opposing their right to build Protestant churches on royal land and destroying their representation at the assemblies, an act which had provoked apoplectic rage amongst the Praguer nobility. On behalf of his class, Count Jindřich von Thurn declared to representatives of Ferdinand II it seemed that total Catholic rule was to begin; shortly after this remark, the representatives were thrown out of a window, beginning the greatest conflict thus far in European history.

The Bohemian revolt is particularly interesting as Bohemia boasted strong artisanal and mining traditions; one of its most important towns was called “Stříbrná Skalice” (Silver Skalitz). Alongside with the region’s record of opposition to the Catholic church (one of Silver Skalitz’s lords, Racek Kobyla of Dvorce, was a key supporter of the Hussites during his own time) this made Bohemia a natural ally of the North Germans. This close relationship was most clearly evidenced when the Elector-Palatine of the Rhine, Friedrich I, the so-called “Winter King” was crowned King of Bohemia in 1619. Friedrich, however, was a Calvinist; his faith had no protections under the status quo of the settlement at Augsburg. The settlement had dissuaded Jan George I of Saxony from rebellion and had given the support of the other major Protestant powers to the Imperial cause. Jan Georg I himself subsequently invaded Bohemia to expand the Saxon realm. Despite its importance, the Bohemian Revolt was fairly brief; Johan t'Serclaes, Graaf van Tilly, the Walloon Field Marshal, devastated the Bohemian forces at White Mountain, bringing the campaign to a decisive end. Friedrich I reigned for only fifteen months.

The next phase of the war went similarly; Friedrich was eventually toppled from his own electorate in the Palatinate. As the war grew, bitter confessional divides served as proxies for conflict over economic interest. The Protestant silver-rich miners of Saxony and Czechia and gold-trading Hansa gave battle against the Catholic wheat farmers of Bavaria and Austria. As the Protestant princes in Germany rebelled against the agrarian favouritism of the Habsburgs, a curious parallel movement, part-Lutheran and part Calvinist, appeared to the south-east in Hungary. The distinction is important, given the state orientation of Lutheranism (under Luther’s argument of the duties of the magistrate, which gave way to a generally interventionist conception of the state) as opposed to the more individualistic orientation of Calvinism, shown in the relative independence of the Dutch state churches compared to their Lutheran counterparts. While on the whole, the predominance of Calvinism among many of the magnates reflected the desire of the Hungarian magnates for autonomy and a more decentralised state against the impositions of Vienna, the vision of a centralist national-state emerged among the more urban Lutherans of Hungary.

Given the heterogeneity and size of Hungary, the divergence in attitudes is unsurprising, but only serves to reinforce our core thesis as expressed in the matrix earlier. The Protestant subversion in Hungary came to a head under Bocskai István, as he waged a war against the Habsburg crown, and succeeded in establishing many rights for the Hungarian nobility. This began the Austro-Hungarian dynamic of internal political struggle that would move back and forth until the end of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Késmárki Thököly Imre, a Lutheran, led another major Protestant rebellion, but the power of Tridentism and the military might of the Austro-Bohemian Catholic alliance was too much to bear. The end of the Thirty Years’ War provided an opportunity for the Habsburgs to reinforce their rule over Hungary, and smash Thököly’s rebellion, thus allowing the Counter-Reformation to take hold in Hungary and quashing Protestantism there. But the Habsburgs had not – could not – quash the separatist sentiments of the Hungarians. Rákóczi Ferenc, a Catholic noble of Calvinist heritage led yet another failed rebellion which forced the Habsburgs to lighten their rule of Hungary, and while Catholicism was clearly the region’s ascendant religion, the Hungarians had secured a settlement of relative political autonomy by the end of our period of study. Could it be that the lack of a durable national state made Hungary Catholic, rather than Protestant, as there were no institutions to defend the country from Habsburg invasion and the Counter-Reformation? An equilibrium was reached in this regard which led to neither a centralised Hungarian national state nor a centralised Habsburg Empire (of which Hungary would have been a constituent part) but rather a rotten compromise which held back the development of the Hungarian state. Arguably, this created an insular and particularist mindset in the Hungarian body politic which still persists to this day.

France

The Grand Siècle (the ‘Great Century’) was the ascendant era of France in its struggle to become a world power, marked by the reigns of Louis XIII (‘the Just’) and Louis XIV (‘the Sun King’). During this period France flourished in the realms of culture, science, art and, most importantly for our purposes, public administration. The key character of this story is not Louis the Just himself, but rather his First Minister, Cardinal Richelieu. Richelieu, alongside his two successors (Colbert and Mazarin), were the founding fathers of the French administrative state. France, over this century, would become the model of absolutism across the continent. Richelieu’s key policies were to increase the taxes on salt and capitation in order to finance French intervention in the Thirty Years’ War with the ultimate goal of grinding down Austro-Spanish hegemony. The financial reforms could also be used in suppressing domestic dissent (the Huguenots) to ensure France continued to be a Catholic country. Richelieu’s policy can thus be summarised as Catholicism at home, Protestantism abroad; a great contradiction. But it proved once again that confession was secondary to the great machines of economic geopolitics, especially as the gamble worked. Catholic France’s alliance to the Protestant princes paid off, and the country became the ascendant power in Europe over the next half-century. Colbert’s administrative and fiscal reforms allowed France to field an army of over 300,000 men by the end of the century. This showed the strength of the French state and marked the beginning of an era of ever-larger armies and mass mobilisation. France moved from an era of consolidation to an era of ascendancy, fighting off further domestic rebellion in the Fronde to establish a very powerful absolutist state which served as the premier land power on the continent for the next century.

Sweden

Sweden, by contrast, was one of two cases of “Lutheran absolutism” (the other being Prussia, which will not be examined here as the moment of their ascendance is outside of our period). The Swedish imperial era - beginning with the ascension of Gustav Adolf and ending with the death of Charles XII at Frederiksten - was one of strong centralisation and the establishment of arguably the most effective fiscal-military state of the early modern era. It laid the progressive foundations of the Swedish public sphere through the disempowerment of the magnates (for example, the Reductions of Charles XI) and the empowerment of a cross-class, pro-absolutist Riksdag to counter the magnate’s own Privy Council. Owing to the great mineral wealth of Sweden, particularly in iron, the mobilisation of a large army relative to its overall population was possible. This made the country a formidable enemy; with Jan Georg I aiding the Swedish advance, the Swedish outnumbered and crushed the Imperial army at Breitenfeld in 1631. At the height of the Great Northern War, Sweden mobilised a hundred thousand men out of a nation of a million and a half: the relative size of this army was incomparable to anywhere else in Europe, barring Prussia alone. It was a testament to the advanced nature of the fiscal-military administration of Sweden that such an army was both raised and funded, and a testament to its quality of drill that it destroyed larger forces at the Second Battle of Breitenfeld and the Battle of Fraustadt. Not for nothing, later in the period, were the so-called “Karoliner” forces known across Europe for their ability to destroy any forces that stood in their path.

Spain

Up to this point, we have left undiscussed one of the great actors of the Thirty Years’ War – Spain. While not facing a large portion of the actual fighting, Spain and its empire were the financiers of the Habsburg war effort, through its gold and silver. But no matter how great the overseas territories, no matter how much the rulers plundered and stole from Latin America, Spain could not conceal its own domestic discontents. The union of the Castilian and Aragonese crowns was not a wholly beautiful nor particularly easy one. Indeed, many of the Catalan nobility resented the overbearing nature of the central state, resulting in the spread of seditious sentiment. The grumbling grew louder after Gaspar de Guzmán y Pimentel, 1st Duke of Sanlúcar, 3rd Count of Olivares’ began his centralising military and economic reforms (the so-called “Union of Arms”) culminating in the outbreak of the Reapers’ War in 1640. The conflict saw centralist France coming to the aid of decentralist rebels, in order to destabilise Spain and the men attempting to centralise it. Here is further evidence states are not as committed to the of spreading a particular ideology as they might like to claim; pragmatic alliance against common enemies demolish the pretences of ideologues. Herein lies the intersection between realpolitik and ideological politics; during the Reaper’s War, the cynicism of the French crown proves ideology and religion are malleable and can be manipulated to serve the needs of various classes and nations.

As in Sweden, in Catalonia the various classes united in a legislative assembly and eventually accepted integration into the centralist Bourbon state. This shows that the interests of particular classes are not per se defined purely by their geography, but also by their relation to the instruments of the state; those within the client framework and those outside it, those within the court and those relegated to be outside it. Even within the Catholic world it seemed the clear difference was still between this side and the other, and it was for this reason that Catholic France fought Catholic Spain alongside the Catholic Catalans. Confession and faith alone cannot explain the conflicts of this century. The Franco-Spanish conflicts resembled far more the terrain in Germany than at once may be admitted by a simple belief that the conflicts in Germany occurred on a religious basis. The divisions in Spain would continue in the coming centuries, finding a second base of conflict in the Carlist Wars, and later the Spanish Civil War, in terms of the conflict between the city and the countryside, between progressivism and conservatism.

Northern Europe

The Polish-Lithuanian case is similar to the Hungarian case in many respects, but unlike the Hungarians, the state maintained a far clearer sense of independence. The examination of our case here will require stepping into the 18th century, but it is nonetheless important to consider in terms of charting the general course of European state development, as in many ways the structure of the Commonwealth and repeated foreign intervention muddied the waters of endogenous development. But in a sense, endogenous development is an illusion - or rather a fragment of modelling. In reality all state-forms are sensitive to the domestic and especially foreign policies of their neighbours through both economic and political mechanisms. This is no clearer than in the case of Poland-Lithuania, where the elective monarchy provided a haven for foreign political interference in its governance. Especially after the Deluge, during which Swedish forces devastated Poland-Lithuania, destroying over half of its GDP in the five years after their own intervention in the Thirty Years’ War, French, Saxon, Russian, Prussian, and Habsburg forces would intervene in the election of the state’s monarchs. Through bribery and other means of corruption, these powers tried to influence the state into adopting a more favourable foreign policy towards them. The most extreme example of this can be seen in the stationing of Russian soldiers in Warsaw, which intimidated the so-called “Dumb Sejm” or “Silent Sejm” into weakening the monarchy significantly, to the detriment of Polish-Saxon King Augustus II. The struggle between Augustus II and the Saxon Court’s supporters - such as the Czartoryskis - and the magnate backers of the Russian Court, would prove to be fatal to the Commonwealth. Its institutions became formless, and consistently rebellious; constant warfare from the Confederations - the legalised rebellions of the szlachta – undermined internal stability and prosperity. The extreme decentralisation of the Commonwealth, particularly its “Golden Freedom” of equality between all nobles, and the Liberum Veto which allowed for a single member of the Sejm to block any new proposal or dissolve the Sejm eventually proved fatal. In terms of our confessional thesis, then, the religious contours map out quite favourably, as Lutherans of Poland - inspired by the Lutheranism of the Saxon Court – tended to back centralisation, while the Catholics tended to oppose it. It was the victory of the Catholics in this matter than allowed the eventual victory of the Russian state. By the end of the 18th century, withStanislaus August II unable to balance both domestic rebellion and foreign influence, partition put the commonwealth out of its misery, and Poland and Lithuania vanished from the map of Europe until the 20th century.

The Protestant Lands

Not all of the decentralised states of Europe were Catholic, however. The heartlands of Reformed Christianity, in the Netherlands, Switzerland, and England, were also the heartlands of commercial proto-liberalism and thus a relatively pluralistic state-form. The institutional support of Calvinism in this regard was essential, as part of the superstructure which supported this form of production. What distinguishes, in particular, the Catholic states from the Calvinist ones? If we have discussed prior - for instance in the Hungarian example - that the class dynamics of centralist bureaucracy favour Lutheranism, and that this was absent in the three states of Reformed Christianity, then what is the contrast between the Polish decentralised state and, for instance, the Dutch decentralised state? In my view, such a distinction emerges from the differing class interest. While the world of traditionalist Catholicism was controlled largely by countryside magnates, the world of Reformed Christianity was controlled by merchants and traders, who existed outside of structures of formal state privilege, which contrasts with the Lutheran cases in North Germany and Sweden, having emerged from proto-corporatist economic policy. The Swiss case in particular is interesting, as the Swiss cantonal structure formed from resistance to Habsburg invasion prior to the Reformation, and as in Czechia under the Hussites, and England under the Lollards, shows the roots of the Reformation not in a sudden theological conversion, but in secular trends surrounding disputes over state power and the class distinctions across and within various states and regions. There is a clear material basis, then, for such distinctions across the continent.

And it is on this soil that we may conclude our examination of the trends of the birth of the modern European state, and in recognising that the varying national characters of the nation-states of modern Europe emerge not from any sort of spirit of history, but rather from unique contours and dynamics of economic development, which transformed themselves into various stripes of centralisation, confession, and politics. It would be a grave mistake to regard these dynamics as discrete or to regard the formation of the European state system as endogenous or incidental. The ground of modernity was laid in the centuries prior, and it is no historical accident, for example, that Hungary is, today, a bastion of conservatism, or Sweden a bastion of social democracy. I have titled this the “Bloody Birth of Europe”, because it is precisely in that trial by fire that the modern peoples of Europe, and the manifestations of their politics, were born. This birth was not glorious nor ordered - it was brutal and it was chaotic. But it is through an understanding of this history that we may understand the ground on which Europe began, and it is now here that we wish to set the further ground on which we may make more specific examinations of the national characters and developmental courses of the nations discussed herein, for the birth of modern Europe was not the birth of a homogenous organism, but instead the birth of a romantic yet inglorious mosaic of peoples, nations, and states.