The Clockwork Orange is Wound in Candlelight: Rumours, Royalty, and Regime Change

‘’We’ll have him out! This time we’ll have him out!’’

- June 1974

It is claimed by Peter Wright that these were the words said to him by two officers of Her Majesty’s Secret Service concerning their institution’s desired removal of Prime Minister Harold Wilson. The Labour government had scarcely been in office for three months, but these officers clearly had already lost their patience. For over a year at this point, Britain had become completely dependent on foreign oil imports, which had quadrupled in price after a total Saudi Arabian embargo placed on the United States. In December 1973, the Financial Times ran the infamous headline ‘The Future Shall be Subject to Delay.’ Britain felt her hands slipping from the crown of a superpower.

The February 1974 election marked somewhat of a watershed for the Conservative Old Guard. Aside from Ted Heath’s loss, a massive shock came when the heavyweight bastion of unflinching Nationalist Conservatism, Enoch Powell, was unseated when the Ulster Unionists splintered from the Tories. Meanwhile, a steady miasma of editorial gunfire had been raining down upon Wilson for the best part of a decade that aimed to convince the British public that he and his ministers were KGB assets. It is remarked that if you tell a man something enough times, no matter how outrageous, he will eventually believe it. It may have indeed been the case that these ‘Old Guard’ types had, by this point, gaslit themselves into believing their own efforts to slander Wilson as a communist spy during the Tories’ effort to win the February 1974 election. Yet, the Old Guard had no plans to cease their activities against Wilson. This was by no means their first attempt to destroy him.

Six years prior, in May 1968, it was alleged that a meeting occurred between media mogul Cecil King, the chairman of the International Publishing Corporation, and Lord Mountbatten of Burma - the uncle of Prince Philip. King was a known participant in his own delusions of grandeur - journalist Geoffrey Goodman, a friend of Wilson, remarked that ‘’he [King] believed he was born to rule’’, and that nothing short of absolute power would satiate King.

Present in the meeting were King, Mountbatten, journalist Hugh Cudlipp, and the Chief Scientific Advisor to Wilson’s government, Sir Solly Zuckerman. King, in his irritability, was alleged by Cudlipp to have begun spouting his grand designs the moment Zuckerman walked through the threshold:

‘’The people would be looking to somebody like Lord Mountbatten as the titular head of a new administration, somebody renowned as a leader of men.’’

Hugh Cudlipp

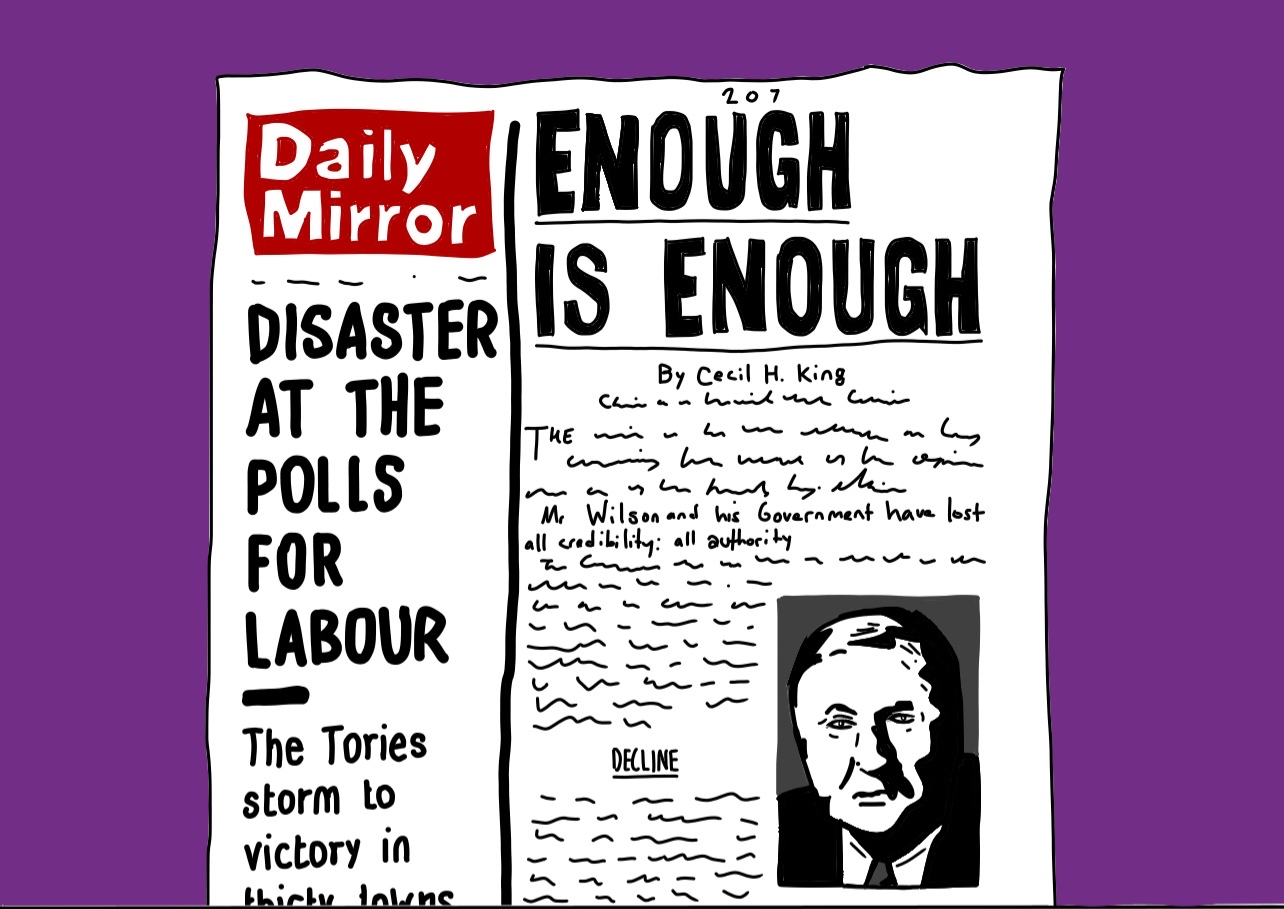

King’s speech also included a list of what he saw as Wilson’s grave and traitorous mistakes, justifications as to why action had to be taken, and that he foresaw mass violence and the involvement of the military. King ended his tirade by asking Mountbatten if he wished to lead this new administration. Mountbatten and Zuckerman slammed King as a ‘traitor’, and promptly stormed out the meeting. King was, however, undeterred. He promptly overrode his editors and emblazoned a scathing rant onto the Daily Mirror’s front page. He wrote that the time had come for Wilson to be removed by extra-parliamentary means, insinuating his support for actions ranging right up to a coup d’état.

King was removed from the board of the IPC by the end of the month, as the board members saw his incitement of regime change as damaging to the reputation of the organisation.

Wilson was defeated in 1970, despite his recent enfranchising of eighteen year olds that led pollsters to place Labour at a predicted 12-point lead. But the Conservatives had little time to breathe. By 1974, amid an escalating economic crisis, he was back. This shook the Old Guard to their core. Inflation was on track to hit twenty-six percent by the next year. Wilson’s perceived socialism would wreck an already fiscally and socially fragile Britain. Something had to be done.

There is the general opinion that the summer season is the riot season - but the summer of 1974 could have gone down with a very different reputation. Officially sanctioned as a counter-terrorism exercise, the army began ‘Operation Marmion’. This operation was intended to rehearse the response to and containment of IRA attacks on vital national infrastructure. In January, while Wilson was leader of the Opposition, the first drill was carried out fully in his knowledge. He expected it to be the last.

But it wasn’t.

In June through to September, the operation was restarted. The army engaged in the seizure of pieces of major national infrastructure, most notably Heathrow Airport, throughout the summer. Travellers were left puzzled seeing soldiers march through terminals and set up checkpoints. So was Wilson. Because, as he claimed in a later memoir, the military was refusing to tell him anything about this. The exercises were supposed to be over in January. It was supposed to be a normal drill.

Yet there was nothing normal about Operation Marmion. Downing Street was locked out of any knowledge of it. After leaving office, Wilson was adamant that the real intention of Marmion had nothing to do with counter-terrorism drills. Instead, it was asserted that the operation was a deliberate show of force towards Wilson’s administration. That the military, and intelligence apparatus, were prepared to move independently if the time came. It was alleged that Marmion instead was a trial run for a nationwide seizure of national infrastructure as part of a coup that would install Lord Mountbatten as the leader. Wilson’s memoirs stressed that during this period, he was painfully aware that he and his government were not in control of either the military or intelligence apparatus. He was clear in his references to the preceding activities as ‘coup attempts’. Tapes recorded shortly after his resignation detail Wilson’s assertion that both serving and ex-military leaders had been assembling provisions in preparation for ‘wholesale domestic liquidation’. Information as to the depth of these preparations is, however, unavailable.

Ultimately, Wilson was never ousted, and instead resigned two years later due to a combination of alcohol addiction and early-onset Alzheimer's. Three years on from Wilson’s resignation, Mountbatten was assassinated using a bomb. And that was, supposedly, it.

In January 1990, a junior minister by the name of Archibald Hamilton admitted before the Commons that a plan by the name of ‘Clockwork Orange’ was very much real. However, he stressed that the plan at no point was ever brought to fruition. Cabinet Secretary Lord Hunt, later in the 1990s, labelled the plot as the pie-in-the-sky work of ‘malcontents in MI5… with serious personal grudges’. The plot was nothing more than a few Old Guard types who got a little desperate as they felt their power slipping away. So it is said, anyway. The scholarship is muddy. The core topic, muddier. It is to be expected that whoever was actually involved would never admit to their part in something so supposedly treasonous.

But what if Clockwork Orange succeeded?

When one thinks of the phrase ‘banana republic’, Britain is not a nation that comes to mind. But what if those ‘malcontents in MI5’, alongside the others, got their way? What would a British Junta actually look like? How would a coup d’état have unfolded?

It is first worth looking at the intended leader of it all, Lord Louis Mountbatten. Would he have ruled like a dictator, or allowed elections down the road? Of course the feasibility of this plot, for the sake of this thought experiment, assumes that Mountbatten did not meet his untimely and explosive end in 1979. This also assumes that Mountbatten’s homosexual and paedophilic tendencies were kept secret. A 2019 release of FBI archives from the 1940s noted Mountbatten’s ‘perversion for young boys’ alongside extreme fetishistic and general sexual depravity towards both sexes. Truly a thoroughly outstanding chap.

Let us assume the public never knew about this, and instead the images of Mountbatten as an elder statesman and war hero were maintained. Mountbatten maintained strong ties with the military, at various points having served as Viceroy of India, First Sea Lord, Chief of Defense Staff, and Commander of NATO’s Mediterranean fleet. In other words, such an employment history would set oneself up well for certain future career ambitions. Stooge-master Cecil King may have been one of Mountbatten’s conduits to the intelligence services. King, aside from his eccentric ambitions, was a known double agent of both MI6 and the CIA. He had operated the CIA-backed magazine ‘Endeavour’, which aimed to promote aggressive foreign policy towards the Soviet Union. A slew of well-known intellectuals and historians were further connected with King’s ‘Endeavour’ - including Isaiah Berlin, Hugh Trevor-Roper, and A.J.P. Taylor. Several affiliates, including Trevor-Roper, were also intelligence operatives.

It is not hard to imagine that in the months leading up to the planned coup, King and his affiliates would have continued to accelerate their media deluge painting Wilson as a Soviet sympathiser. Since 1945, MI5 had kept files on Wilson due to this exact suspicion, though nothing concrete was ever discovered to suggest he had betrayed his country. The memory of the Profumo affair a decade earlier was still fresh - senior government officials being blackmailed or turned was not some mere fantasy.

Over the winter, it is plausible that the security services would embolden trade unions to agitate, producing further social and economic instability. This is not a far-fetched idea. In 1987, former MI5 officer James Miller alleged that a 1974 strike of the Ulster Workers’ Council was backed by the intelligence services to destabilise Wilson’s government. Widespread civil unrest and strike action would bog down local law enforcement, lead to outages of basic amenities including electricity, and distract the eyes of the government from the continued winding of the Clockwork Orange.

By the summer, it would have been time for Marmion to commence. Except on this occasion, one could say for certain it was no exercise. Unlike the hollowed-out institution of today, in the 1970s, the British army alone wielded around a quarter of a million personnel. The nation’s power generation, railways, airports, major roads, and other important infrastructure would be taken from civilian control and administered directly by the military. It is likely that in the face of continued agitation by trade unions, public opinion may have indeed welcomed such actions. This factor alone would be used to further discredit the government, and make public opinion more supportive of the actions of the plotters.

Now in control of the nation’s infrastructure, the coup plotters would have possessed a range of cards to play. One option may have simply been as follows - use your control of roads, trains, and airports to enact economic blackmail far more damaging than any union could ever dream of. Threaten the government by saying you will shut down national supply chains, and therefore the economy, unless either a general election is called or Mountbatten is installed. Given the saying that men are always three meals away from revolution, this would likely have been fast, effective, and mostly bloodless in reaching the desired ends.

Another option is just a good old-fashioned show of force. Roll the tanks into the capital. You control the roads, rails, and runways, so nobody leaves or enters. Issue a final warning that reads something like ‘Dear Mr Wilson. Please resign or be the first person to experience whether all those weird allegations against Mountbatten are real. Love and hugs.’

Wilson leaves. If the plotters are feeling nice, he will get the Nikita Khrushchev treatment and be allowed to live out the rest of his days locked up in a cabin somewhere remote. If the plotters woke up on the wrong side of the bed, the reader can fill in the rest for themselves.

By 1974 Wilson was a deeply embattled man - forcing a resignation may have been easier than expected.

Mountbatten is now in charge. Using his stooge footsoldiers, Mountbatten either floods the media zone with information that aims to quell public doubt, or enacts a media blackout. Britain soon finds herself under international condemnation, and perhaps even trade embargos from the European common market, which Britain entered into at the beginning of 1974. Unfortunately for the plotters, the Americans are busy with the Watergate Scandal. Yet fortunately for Mountbatten, a certain Henry Kissinger would stay on as National Security Advisor and Secretary of State even after Nixon resigned in August 1974. Kissinger was already supporting the Chilean Junta of Augusto Pinochet from 1973, and also planned to support the Argentine Junta in the Dirty War. Kissinger did a great job of being the ultimate wingman for military juntas. The one in Argentina got self-confident in 1982 that it decided to try it on with the British. But Kissinger was not quite good enough to prevent the British administering an ass-whooping so severe it would lead to the Argentine regime’s collapse after.

Mountbatten would have his men, and his moment. With friends in the White House, an oil crisis in the Gulf, and China still reeling from the Cultural Revolution, Mountbatten at this point would have to trust that the international community would eventually stop caring that the democratically elected government of one of the world’s most powerful nations was just overthrown. Over the coming months, trade sanctions and official condemnations would be quietly lifted.

If the plotters had sense, then their seizure of public sentiment towards the persistent disruption by trade unions would be the keystone of their domestic sustainability. Simply put, the propaganda spin would emphasise how the lights stayed on, the roads stayed clear, and the trains actually ran under the new regime. If this all appeared to be working, then elections could go ahead with approved candidates to further legitimise the new administration. And thus, democracy would be fully dead and buried by the end of the decade. One wonders how much of the public would have actually missed it.

Of course, this is all just a silly thought experiment in an alternate history of this nation, combined with some actual history. The reality was far different. By 1980 we still had democracy. We still had the ballot box. What was left of Mountbatten ended the decade in a slightly different box. But perhaps we may still award him a participation trophy.

History is immensely enjoyable when ‘what was’ is examined. It is equally enjoyable when ‘what if’ is also considered. Let us be thankful this instance of ‘what if’ never fully materialised. The Clockwork Orange stays unwound. For now.